La politique est l’art du possible [1]. Dans leur manuel de Droit constitutionnel et institutions politiques, Jean Gicquel et son fils Jean-Éric Gicquel commencent à définir la politique par cette expression courante. Ils n’ont pas tort d’ouvrir l’explication de cette notion par la définition la plus large possible étant donné tous les sens qu’elle peut recouvrir. Le terme politique vient du grec polis qui signifie «cité». Le sens ordinaire de ce terme, quand il est employé au féminin, serait «l’art de gouverner la cité, de diriger l’Etat» [2].

Jean et Jean-Éric Gicquel se sont appliqués à dégager les différentes acceptions que ce terme peut avoir. Dans une acception restrictive, la politique désignerait «l’action» ou encore «le programme d’un homme, d’un parti, d’un Gouvernement, d’un Etat…». Ce serait alors «une activité ou un secteur spécifique, mieux irréductible, par rapport aux autres activités ou secteurs d’une société» et cette activité serait «celle d’une minorité (la classe politique)». Dans une acception extensive, «la politique se rapporte aux individus vivant en société, l’Etat apparaissant, en définitive, comme la société des sociétés». Définie ainsi, la politique ne serait plus une activité spécialisée mais, au contraire, serait «banalisée, la chose de toutes et tous» [3].

Il y a deux choses à extraire de ces définitions de la politique. Premièrement, l’analyse de la dépolitisation de l’Etat implique de rejeter de l’étude l’acception extensive étant donné que l’Etat, la société des sociétés, n’y est pas pris en compte. Deuxièmement, ne retenant que l’acception restrictive, la politique impliquerait des décisions, la décision étant définie comme un «acte par lequel quelqu’un opte pour une solution, décide quelque chose» [4]. Effectivement, l’action est le «fait ou faculté d’agir, de manifester sa volonté, en accomplissant quelque chose» [5] ce qui suppose a priori de prendre une décision. Il en va de même pour le «programme», lequel est un «ensemble des projets, des intentions d’action de quelqu’un, d’un groupe, d’un parti politique, etc» [6] car l’homme, le parti, le gouvernement ou l’Etat ont, pour composer un programme, le choix entre plusieurs orientations possibles.

La politique est donc bien l’art du possible en ce qu’elle implique la possibilité de prendre des décisions choisies en fonction de plusieurs orientations possibles. A l’inverse, la dépolitisation diminuerait donc la quantité des orientations et choix possibles face à la potentielle prise de décision. Et ce phénomène agit de plus en plus sur l’autorité politique de l’Etat français.

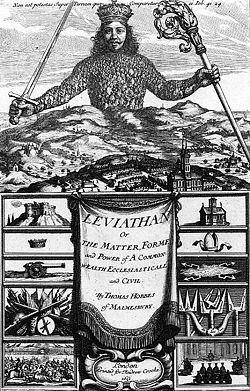

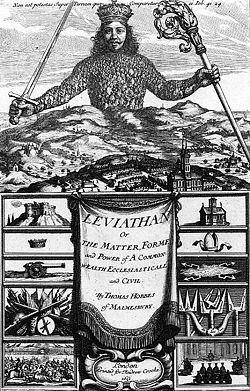

Selon le Vocabulaire juridique de Gérard Cornu, l’Etat est une «entité juridique formée de la réunion de trois éléments constitutifs (population, territoire, autorité politique) et à laquelle est reconnue la qualité de sujet du Droit international. Groupement d’individus fixé sur un territoire déterminé et soumis à l’autorité d’un même gouvernement qui exerce ses compétences en toute indépendance en étant soumis directement au droit international» [7].

D’après cette définition, l’autorité politique (qui est l’élément constitutif qui intéresse le plus notre étude) serait donc un unique gouvernement, exerçant ses compétences en toute indépendance, étant soumis directement au droit international et soumettant la population fixée sur le territoire qu’il régit.

Cette autorité politique, Jean Gicquel et Jean-Éric Gicquel vont plus loin en la nommant l’autorité politique exclusive ou la souveraineté [8]. Pour eux, «l’Etat est constitué et traité en cette qualité, lorsqu’il exerce, de manière effective, sur la population rassemblée en un territoire déterminé, une autorité politique exclusive, appelée la souveraineté. En d’autres termes, cette dernière implique la négation de toute entrave, de toute subordination vis-à-vis d’un autre Etat, en dehors des limitations librement acceptées. A ce titre, l’Etat dispose de la compétence de sa compétence (Jellinek). Il suit de là, que la souveraineté est l’apanage de l’Etat, à l’opposé des organisations internationales (O.N.U., Union européenne) qui ne peuvent bénéficier que de transferts de compétences (C.C., 9 avril 1992, Traité sur l’Union européenne, chr. n°62, p.182)» [9].

Cette explication est très importante pour deux raisons. La première est qu’elle éclaircit la notion de souveraineté en montrant sa double définition. D’abord, il y a la souveraineté de l’Etat dite extérieure et théorisée par Jean Bodin en 1576 dans De la République qui est «absolue, perpétuelle, au-delà des individus qui l’incarnent et indivisible, en ce qu’elle se rapporte à un seul titulaire, qu’il s’agisse d’un être individuel (le roi) ou collectif (le peuple)» [10]. Ensuite, il y a la souveraineté dans l’Etat dite intérieure consistant «à admettre que la souveraineté est la manifestation de la volonté spécifique de l’Etat. Celui-ci assume seul un certain nombre d’attributs (les marques de souveraineté pour Bodin) : droits de législation et de réglementation, de justice, de police, de battre monnaie, de légation, de lever et d’entretenir une armée, d’accéder à la fonction publique et celui de conférer la nationalité entre autres. Ainsi l’Etat exerce une compétence tout à la fois à l’égard du territoire auquel il s’identifie et des personnes qui s’y trouvent rattachées» [11].

La deuxième raison qui rend importante l’explication de Jean et Jean-Eric Gicquel est qu’elle permet de montrer le vrai sens juridique de la notion de souveraineté souvent détournée au profit d’un sens plus politicien. En effet, il est courant d’entendre que «l’Etat français a perdu sa souveraineté à cause de l’Union européenne». Ceci, théoriquement (c’est-à-dire dans la définition publiciste du terme), est faux et l’explication permettra de justifier le terme de dépolitisation utilisé pour notre étude.

Tout d’abord, dire qu’un Etat n’est plus souverain est contradictoire puisque sans souveraineté point d’Etat. Aussi, l’Union européenne n’est pas un Etat mais une organisation internationale, c’est-à-dire un «groupement permanent d’Etats doté d’organes destinés à exprimer, sur des matières d’intérêt commun, une volonté distincte de celle des Etats membres» [12]. Ainsi, l’Etat français n’est pas subordonné à un autre Etat.

Ensuite, en vertu de l’article 54 de la Constitution, le Conseil constitutionnel peut être amené à contrôler la compatibilité des traités avec la Constitution avant leur ratification. Il peut aussi exercer ce contrôle a priori par le biais du contrôle des lois de ratification des traités au titre de l’article 61 de la Constitution. Cela montre donc la supériorité de la Constitution sur les engagements internationaux et le droit communautaire originaire. Ceci a été réaffirmé à la fois par le juge administratif et le juge judiciaire (CE, Ass., 3 juillet 1996, Koné ; CE, Ass., 30 octobre 1998, Sarran ; C.Cass., Ass., 2 juin 2000, Ass. plén. Mlle Fraisse). Enfin, ce n’est pas parce que les traités priment sur les lois et les normes infra-législatives (C. Cass. J. Vabre, 1975 ; C. Const. Elections législatives du Val d’Oise, 1988 ; CE, Nicolo, 1989) que l’Etat n’est plus souverain.

En effet, «la faculté de contracter des engagements internationaux est précisément un attribut de la souveraineté de l’Etat» (CPJI, arrêt du 17 août 1923, Affaire du Vapeur Wimbledon, série A, n°1, p.25). Non seulement l’Etat est libre de conclure une convention internationale mais c’est aussi et surtout parce qu’il est souverain qu’il peut librement conclure des conventions internationales. Certes, comme le dit l’adage, pacta sunt servanda. Mais l’Etat peut très bien dénoncer ou se retirer d’une convention internationale qu’il a lui-même librement conclue si le traité le prévoit (ce que permet l’article 50 de la version consolidée du Traité sur l’Union Européenne depuis le traité de Lisbonne signé en 2007). Si le traité ne le prévoit pas, il faut qu’il soit établi qu’il entrait dans l’intention des parties d’admettre la possibilité d’une dénonciation ou d’un retrait ou encore que le droit de dénonciation ou de retrait puisse être déduit de la nature du traité (article 56 de la Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969).

Il ne s’agit pas de légitimer tel ou tel traité conclu par l’Etat français mais plutôt d’éclaircir la notion de souveraineté afin de justifier l’angle utilisé (la dépolitisation) pour analyser les causes de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat français actuel. Effectivement, il est courant d’entendre que si l’Etat est désormais faible politiquement c’est parce qu’il «n’est plus souverain». Or, comme nous venons de le voir, l’Etat français – qui a certes perdu son indépendance économique – est toujours souverain (sinon, on ne devrait même plus parler d’Etat). Aussi, ramener le problème de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat au seul problème de la souveraineté occulterait de l’analyse un bon nombre de causes de cette faiblesse.

Il ne s’agit pas de légitimer tel ou tel traité conclu par l’Etat français mais plutôt d’éclaircir la notion de souveraineté afin de justifier l’angle utilisé (la dépolitisation) pour analyser les causes de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat français actuel. Effectivement, il est courant d’entendre que si l’Etat est désormais faible politiquement c’est parce qu’il «n’est plus souverain». Or, comme nous venons de le voir, l’Etat français – qui a certes perdu son indépendance économique – est toujours souverain (sinon, on ne devrait même plus parler d’Etat). Aussi, ramener le problème de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat au seul problème de la souveraineté occulterait de l’analyse un bon nombre de causes de cette faiblesse.

Un Etat dépolitisé signifie qu’il est de moins en moins apte à prendre les décisions de son choix car la quantité des orientations et choix possibles face à la potentielle prise de décision serait de plus en plus faible. Certes, dans ses décisions, un Etat peut être parfois ponctuellement contraint (face à l’agression d’un Etat tiers, un Etat est contraint de se défendre) mais avec le phénomène de dépolitisation la contrainte n’est plus ponctuelle mais continue et touche de plus en plus de prérogatives de l’Etat.

L’Etat français actuel est un Etat dit «de droit» (dans une conception à la fois matérielle et formelle), c’est-à-dire «un Etat dont l’ensemble des autorités politiques et administratives, centrales et locales, agit en se conformant effectivement aux règles de droit en vigueur et dans lequel tous les individus bénéficient également de garanties procédurales et de libertés fondamentales» [13]. Rien que le fait que l’Etat français soit un Etat de droit limite la capacité de l’autorité politique de décider conformément à ses choix puisqu’elle reste soumise au droit (que cela soit bien ou mal, peu nous importe). Il en est par exemple ainsi quand le conseil constitutionnel déclare non conforme à la Constitution des dispositions d’un projet ou d’une proposition de loi, pourtant fruits d’une décision du gouvernement ou du Parlement.

Le phénomène de dépolitisation de l’Etat est donc à analyser d’un point de vu plus global que le seul problème de l’Union européenne et du droit international en général (bien qu’il entre largement en compte).

I] UN ETAT IMPUISSANT

Impuissant est devenu l’Etat français à la fois à cause de sa soumission au droit européen mais aussi à cause de son objectivation par le droit.

LA DOMINATION DU DROIT EUROPEEN SUR LE DROIT INTERNE

La dépolitisation de l’Etat français s’effectue en grande partie par la domination du droit européen (autant celui de l’Union européenne que celui de la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme) sur le droit interne. Le droit dérivé de l’Union européenne (UE) est composé des recommandations et avis qui n’ont pas de valeur contraignante, des règlements qui ont une portée générale et qui sont obligatoires et directement applicables dans tous les Etats membres, ainsi que des directives qui lient l’Etat seulement quant au résultat à atteindre.

Conformément à l’article 3 du Traité sur le Fonctionnement de L’Union Européenne (TFUE), «l’Union dispose d’une compétence exclusive dans les domaines suivants : l’union douanière, l’établissement des règles de concurrence nécessaires au fonctionnement du marché intérieur, la politique monétaire pour les Etats membres dont la monnaie est l’euro, la conservation des ressources biologiques de la mer dans le cadre de la politique commune de la pêche, la politique commerciale commune» ou enfin «pour la conclusion d’un accord international quand cette conclusion est prévue dans un acte législatif de l’Union, ou est nécessaire pour lui permettre d’exercer sa compétence interne, ou dans la mesure où elle est susceptible d’affecter les règles communes ou d’en altérer la portée».

Conformément à l’article 4 du même traité, «les compétences partagées entre l’Union et les Etats membres s’appliquent aux principaux domaines suivants : le marché intérieur, la politique sociale» (seulement pour les aspects définis dans ledit traité) «la cohésion économique, sociale et territoriale, l’agriculture et la pêche» (sauf pour la conservation des ressources biologiques de la mer), «l’environnement, la protection des consommateurs, les transports, les réseaux transeuropéens, l’énergie, l’espace de liberté, de sécurité et de justice, les enjeux communs en matière de santé publique» (seulement pour les aspects définis dans ledit traité).

En vertu de l’article 5 du TFUE, l’Union dispose aussi de compétences de coordination dans le domaine économique mais aussi de l’emploi et des politiques sociales. Enfin, l’article 6 explique que «l’Union dispose d’une compétence pour mener des actions pour appuyer, coordonner ou compléter l’action des Etats membres», les domaines de ces actions étant «la protection et l’amélioration de la santé humaine, l’industrie, la culture, le tourisme, l’éducation, la formation professionnelle, la jeunesse et le sport, la protection civile, la coopération administrative».

Ainsi les domaines de compétences pour lesquels l’UE peut agir par le biais de son droit dérivé sont fort nombreux. Aussi, en vertu du principe de primauté du droit de l’UE sur le droit interne, ce dernier doit se soumettre au premier (CJCE, 15 juillet 1964, Costa c. E.N.E.L.), ce que rappelle la déclaration n°17 annexée à l’Acte final du Traité de Lisbonne (à condition, bien sûr, que l’UE agisse dans le cadre de ses compétences conférées par son droit originaire).

Les conséquences de ce principe dans le droit interne sont nombreuses. Par exemple, avec l’arrêt d’Assemblée Nicolo du 20 octobre 1989, le Conseil d’Etat a contrôlé la compatibilité d’une loi avec le droit originaire européen (en l’espèce le Traité de Rome). Cette décision s’est ensuite appliquée au droit communautaire dérivé (CE, 24 septembre 1990, Boisdet ; CE, 28 février 1992, SA Rothmans International France ;…). Aussi, le juge administratif a jugé que le gouvernement devait s’abstenir de prendre les actes réglementaires d’application d’une loi quand cette dernière est incompatible avec les objectifs d’une directive (CE, 24 février 1999, Association de Patients de la médecine d’orientation anthroposophique). Les autorités de l’Etat ne peuvent après l’expiration des délais impartis de transposition de directives «laisser subsister des dispositions réglementaires qui ne seraient plus compatibles avec les objectifs définis par les directives» (CE, 3 février 1989, Compagnie Alitalia). Bref, nous pourrions allonger cette liste qui n’est pas exhaustive.

En ce qui concerne la Convention Européenne des Droits de l’Homme (CEDH) adoptée dans le cadre du Conseil de l’Europe le 4 novembre 1950 et qui regroupe à présent quarante-six Etats dont la France, elle permet aux individus d’invoquer directement les droits qu’elle contient devant le juge interne et permet aux particuliers par le biais d’un mécanisme juridictionnel d’exercer un recours devant la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme contre leur Etat si celui-ci n’a pas respecté leurs droits contenus dans la CEDH et si toutes les voies de recours interne ont été épuisées. Pour ne citer qu’un exemple parmi bien d’autres, c’est ainsi que la France a déjà été condamnée pour une loi que le Conseil constitutionnel avait estimé conforme à la Constitution (CEDH, 28 octobre 1999, Zielinski et Pradal et autres c. France). Dans son dernier rapport datant de 2014, la Cour a compté le nombre d’arrêts qui ont jugé des violations de la CEDH pour chaque Etat partie de 1959 à 2014. L’Etat français a été condamné neuf cent trente-cinq fois.

UN ETAT «OBJECTIVE» PAR LE DROIT

L’Etat n’est plus décisionniste mais est au contraire complètement objectivé par le droit. Hans Kelsen a eu beaucoup d’influence dans l’objectivation de l’Etat par le droit puisque pour lui l’Etat et l’ordre juridique ne font qu’un [14]. C’est ce qui conduit Carl Schmitt a expliqué que Kelsen pense qu’ «aux yeux du droit, l’Etat doit être une réalité purement juridique, ayant valeur normative, donc nullement une réalité ou une idée à côté et en dehors de l’ordre juridique, mais précisément rien d’autre que cet ordre juridique même, et naturellement comme une unité» [15]. L’Etat et droit ne font donc qu’un. L’Etat n’est pas la source du droit.

Pour fonder sa Théorie pure du droit Kelsen se fonde sur un dualisme opposant le Sein au Sollen c’est-à-dire le «fait» au «devoir-être». Tout ce qui est une volonté, une décision relève du Sein tandis que la norme relève du Sollen : «la norme est un «devoir être» (Sollen), alors que l’acte de volonté dont elle est la signification est un «être» (Sein)» [16]. Mais pour qu’il y ait une norme (Sollen) il faut un acte de volonté (Sein) qui la pose. Néanmoins pour que le Sollen soit une norme il faut qu’il soit objectif, et pour cela il faut que l’acte de volonté (qui relève du Sein) posant le Sollen soit habilité par une norme supérieure (la Constitution). Ainsi ce n’est pas l’acte de volonté qui fait le droit mais le droit qui identifie le Sollen que pose l’acte de volonté comme objectif et donc comme étant une norme [17].

Si Kelsen évacue le problème de la souveraineté [18] c’est parce que pour lui le fait (la décision) ne crée pas directement de la norme. Pour Kelsen, toute norme doit être prise conformément à la Constitution elle-même légitimée par une fiction qui n’existe pas : la norme fondamentale. Cela amène plusieurs remarques.

D’abord, au-delà de l’identité entre Etat et droit, ce serait en fait le droit seul qui primerait sur l’Etat le réduisant alors à n’être que son fidèle serviteur et pas l’inverse. C’est ce qui amène Carl Schmitt à expliquer que «la théorie du primat de l’ordre juridique de l’Etat, il [Kelsen] l’appelle «subjectiviste» : c’est pour lui une négation de l’idée de droit, car elle a mis le subjectivisme du commandement à la place de la norme, qui a valeur objective» [19]. Ensuite à force de nier la souveraineté sa théorie présente un défaut. En effet, imaginons que demain un coup d’Etat militaire se produise en France : ce coup d’Etat serait parfaitement irrégulier au regard de la Constitution. Pourtant, ces militaires fonderaient un nouvel ordre juridique auquel la population devrait se conformer. Un fait, une décision, relevant alors du Sein produirait donc directement des normes qui au regard de l’ordre juridique renversé n’en constituent pas. Imaginons aussi qu’il y ait une guerre civile en France : le Président de la République, appliquant l’article 16 de la Constitution, exerce les pleins pouvoirs. Après trente jours d’exercice des pouvoirs exceptionnels le Conseil constitutionnel saisi par le Président du Sénat, le Président de l’Assemblée nationale, soixante députés ou soixante sénateurs, émet un avis dans lequel il explique que les pleins pouvoirs ne sont plus légitimés. Imaginons alors que le Président de la République continue quand même à les exercer alors qu’il n’est plus habilité à le faire selon la Constitution : ses décisions créent directement des normes. C’est en cela qu’il faut comprendre la fameuse formule de Carl Schmitt : «Est souverain celui qui décide de la situation exceptionnelle» [20] ou plutôt «Est souverain celui qui décide lors de la situation exceptionnelle» [21].

Cette objectivation de l’Etat par le droit le dépolitise, la politique appartenant de toute façon au domaine du Sein. Puisque selon Kelsen droit et Etat ne font qu’un, la politique est évacuée de l’Etat. Cette objectivation de l’Etat par le droit est accentuée par le fait que les décisions de l’Etat français sont en partie soumises au droit de l’Union européenne, c’est-à-dire un droit qui n’est pas produit par lui-même mais qu’il se doit quand même d’appliquer.

L’exemple de la métamorphose du service public français est révélateur. Alors que ce dernier était une réponse à des aspirations sociales comme le besoin de solidarité, sa spécificité française est cassée afin de conformer son mode de financement au droit et aux intérêts économiques de l’Union européenne.

En effet, selon l’article 107 du Traité sur le Fonctionnement de l’Union Européenne (TFUE), «sauf dérogations prévues par les traités, sont incompatibles avec le marché intérieur, dans la mesure où elles affectent les échanges entre États membres, les aides accordées par les États ou au moyen de ressources d’État sous quelque forme que ce soit qui faussent ou qui menacent de fausser la concurrence en favorisant certaines entreprises ou certaines productions». Mais ces aides sont indispensables pour le financement des services publics qui ne poursuivent pas un objectif de pure rentabilité économique. C’est ainsi que la Cour de Justice des Communautés européennes a rendu un arrêt Altmark le 24 juillet 2003 dans lequel elle établit quatre critères qui, s’ils sont remplis, font échapper la mesure de financement visée à la qualification d’aide d’Etat de l’article 107 du TFUE. Ces quatre critères cumulatifs sont que, premièrement, les obligations de service public doivent être clairement définies. Deuxièmement, les critères et paramètres permettant d’établir cette compensation doivent préalablement être établis de manière objective et transparente. Troisièmement, le montant de la compensation doit être proportionnel aux coûts occasionnés par l’exécution des obligations de service public. Quatrièmement, le montant de la compensation doit être déterminé sur la base d’une analyse des coûts qu’une entreprise moyenne et correctement gérée devrait supporter pour remplir des missions analogues.

Le financement du service public français par l’Etat doit donc désormais remplir certains critères pour ne pas trop gêner la concurrence libre et non faussée promue par l’Union européenne. L’Etat français est donc objectivé en partie par un droit de plus en plus gestionnaire qui guide ses prises de décisions. L’Etat devient donc inconsistant et involontaire.

II] UN ETAT GESTIONNAIRE

Julien Freund, dans un article sur la pensée de Carl Schmitt, expliquait que l’on entrait dans le règne de la politique non politique [22] à cause du phénomène de technicisation de ce qu’on présente comme étant de la «politique». Ce phénomène est accentué par ce que j’appellerais le coup d’Etat du management.

L’ERE DE LA «POLITIQUE NON POLITIQUE»

Comme l’explique Julien Freund, «la technique joue la carte du fonctionnalisme axiologiquement neutre ; elle se présente comme pure instrumentalité douée de la compétence, jusqu’à se faire passer pour une «politique non politique», c’est-à-dire dans le langage qui a cours de nos jours, pour une politique non politicienne. Il va presque de soi qu’elle cherche sa légitimité ailleurs qu’au Parlement, dans un autre type de rationalité, celui du prestige de l’efficacité et de la compétence au sein d’un monde de plus en plus complexe, irréductible à une norme générale» [23].

Ce constat est juste. Les hommes politiques actuels ne parlent que de problématiques économiques au sens technique du terme. La crise économique le justifiant, ils ne parlent que de chômage, de pouvoir d’achat, de consommation, de croissance, de déficits budgétaires à combler, d’inflation et autres problèmes très terre-à-terre qui apparaissent comme étant les plus neutres possibles. Quelle que soit la majorité au pouvoir, les problématiques sont toujours les mêmes et les réponses à peu près semblables. Ce phénomène est accentué par le fait que les politiciens au pouvoir, de «droite» ou de «gauche», viennent pour beaucoup de la même école : l’Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA) formant désormais les technocrates en puissance.

Cette apparente neutralité peut s’illustrer facilement par le comportement, le parcours et le discours de certains technocrates. L’exemple le plus révélateur est sans doute celui de Jacques Attali. Enarque, ancien conseiller spécial de François Mitterand, il conseille désormais tantôt des hommes politiques dits de «gauche», tantôt des hommes politiques dits de «droite» pour leur donner les mêmes solutions aux mêmes problématiques soulevées. Nous pouvons aussi prendre l’exemple de son protégé, Emmanuel Macron, lui aussi ancien élève de l’ENA et désormais ministre de l’Economie, qui a déclaré que l’élection des hommes politiques était désormais «un cursus d’un ancien temps» et que sur le plan de la politique économique il pouvait y avoir «beaucoup de convergences entre la gauche de gouvernement et la droite de gouvernement» [24].

L’ère de la politique non politique est donc une uniformisation des décisions des acteurs politiques apparaissant comme neutres car relevant de la simple gestion d’un système économique libéral se présentant comme étant le seul possible. There is no alternative ou la fameuse formule attribuée à Margaret Thatcher est malheureusement la véritable croyance de nos petits technocrates actuels et cette croyance a largement accéléré le processus de dépolitisation de l’Etat.

L’ère de la politique non politique est donc une uniformisation des décisions des acteurs politiques apparaissant comme neutres car relevant de la simple gestion d’un système économique libéral se présentant comme étant le seul possible. There is no alternative ou la fameuse formule attribuée à Margaret Thatcher est malheureusement la véritable croyance de nos petits technocrates actuels et cette croyance a largement accéléré le processus de dépolitisation de l’Etat.

A l’ère de l’Etat objectivé par le droit et de la démocratie libérale qui se donne pour seul objectif de réaliser les voeux pieux de paix et d’égalité, les technocrates sont tombés dans le camp du positivisme idéologique appliquant un droit gestionnaire de manière automatique. Ces hauts fonctionnaires devenus de véritables automates sont aussi, pour une bonne partie de leur activité, de simples exécutants du droit de l’Union européenne. Partant tous du seul postulat qu’un seul système est possible, la politique présupposant des décisions se dissout alors dans de la pure gestion.

LE COUP D’ETAT DU MANAGEMENT

Moderniser et rendre efficace l’administration de l’Etat sont désormais les maîtres-mots de nos technocrates. A partir des années 1960, les Etats-Unis ont lancé le mouvement du mangement public sous le nom de Planning Programming Budgeting System (PPBS) traduit en français par la Rationalisation des Choix Budgétaires (RCB). Ce plan servait à «préciser des critères de choix, comparer les divers objectifs souhaités et les divers moyens de les atteindre, mesurer avec une approximation suffisante le coût total des actions à engager et les avantages que l’on peut en attendre, peut-être plus tard, agréger ces mesures et ces comparaisons non pas seulement dans le cadre d’un ministère mais au sommet, entre les missions diverses de l’Etat, raisonner pour ce faire non plus dans le cadre traditionnel de l’annualité mais dans une perspective à plus long terme» [25].

Le coup d’Etat du management s’est opéré progressivement. Par une circulaire du 23 février 1989 relative au renouveau du service public l’accent devait être mis sur le développement des responsabilités des agents publics ainsi que sur l’évaluation des politiques publiques. Par le biais de projets de service il fallait «mettre en évidence les valeurs essentielles du service, clarifier ses missions, fédérer les imaginations et les énergies autour de quelques ambitions». Par une circulaire du 28 décembre 1998 relative à l’évaluation des politiques publiques, Lionel Jospin alors Premier Ministre demande à tous les ministres et secrétaires d’Etat de son gouvernement «de renforcer la capacité de [leurs] administrations à évaluer les politiques dont [ils ont] la charge ou qui sont déléguées à des établissements publics placés sous [leur] tutelle. Dans cette perspective, [ils désigneront] un haut fonctionnaire en charge de l’évaluation au sein de [leur] département, qui sera le correspondant du Commissariat général du Plan et du Conseil national de l’évaluation». En 1994 un rapport sur «L’Etat en France» ainsi qu’une circulaire du 26 juillet 1995 relative à la préparation et à la mise en oeuvre de la réforme de l’Etat et des services publics ont approfondi cette démarche de rationalisation et de modernisation de l’administration. Un décret du 30 décembre 2005 a créé la Direction générale de la modernisation de l’Etat sous l’autorité du ministre de l’économie, des finances et de l’industrie. En 2008, un rapport publié par la documentation française sous le titre de 300 décisions pour changer la France et produit par la Commission pour la libération de la croissance française présidée par Jacques Attali proposait des réformes pour moderniser l’administration dont la suppression des départements.

La loi organique du 1er août 2001 relative aux lois de finances (LOLF) prévoit un budget de l’Etat dans lequel les crédits sont regroupés dans des programmes, eux-mêmes regroupés dans des missions. Le programme «regroupe les crédits destinés à mettre en oeuvre une action ou un ensemble cohérent d’actions relevant d’un même ministère et auxquels sont associés des objectifs précis, définis en fonction de finalités d’intérêt général, ainsi que des résultats attendus et faisant l’objet d’une évaluation». La mission quant à elle «comprend un ensemble de programmes concourant à une politique définie» (article 7 de la loi). Un budget de moyens est ainsi remplacé par un budget d’objectifs. «Il faut s’engager sur des objectifs précis, rendre compte chaque année de ses résultats et donc afficher une gestion performante» [26]. Après la mise en application totale de la LOLF à partir du 1er janvier 2005, une communication en conseil des ministres annonce le 20 juin 2007 la Révision Générale des Politiques Publiques (RGPP) «consistant à passer en revue l’ensemble des politiques publiques pour déterminer les actions de modernisation et d’économies qui peuvent être réalisées» avec comme axes de modernisation «des administrations recentrées sur le cœur de leurs missions, des procédures plus modernes, au service des usagers, un État réorganisé et allégé, un État mieux géré, qui valorise le travail des fonctionnaires et qui utilise au mieux les ressources publiques» [27]. Enfin, le 1er octobre 2012, le Premier ministre Jean-Marc Ayrault a convoqué un séminaire sur la Modernisation de l’Action Publique (MAP) censée succéder à la RGPP bien qu’elle suit la même logique de réformer l’Etat dans un but de modernisation et d’efficacité afin de baisser les dépenses publiques.

Le coup d’Etat du management a donc imprégné l’Etat d’une logique d’entreprise recherchant avant tout l’efficacité et la rationalité à travers un processus appelé modernisation. Cette modernisation dépolitise largement l’Etat étant donné que les décisions des acteurs politiques sont alors limitées et encadrées par des règles visant à les faire coûter le moins cher possible. Rationnaliser les dépenses de l’Etat n’est pas critiquable en soi : ce qui est critiquable est de le normaliser en le conformant à des logiques d’entreprise alors qu’un Etat doit au contraire conserver ses prérogatives et attributs exceptionnels (l’Etat ne doit pas être normal et il en va de même pour son Chef). Aussi, il s’agit encore une fois de soumettre l’Etat, présenté comme le boulet qui coûte trop cher, au système libéral mondialisé. Ce coup d’Etat du management contribue à dissoudre la politique dans l’économisme et la technique.

III] UN ETAT AFFAIBLI PAR LE LIBERALISME

Le libéralisme défie l’Etat car ce dernier est vu comme une contrainte pour les libertés individuelles. Il l’affaiblit pour le sacrifier sur l’autel du Progrès.

LE LIBERALISME, ENNEMI DE L’ETAT

Il me faut ici convoquer Carl Schmitt, grand critique du libéralisme. «Très systématiquement, la pensée libérale élude ou ignore l’Etat et la politique pour se mouvoir dans la polarité caractéristique et toujours renouvelée de deux sphères hétérogènes : la morale et l’économie, l’esprit et les affaires, la culture et la richesse. Cette défiance critique à l’égard de l’Etat et de la politique s’explique aisément par les principes d’un système qui exige que l’individu demeure terminus a quo et terminus ad quem. L’unité politique doit exiger, le cas échéant, que l’on sacrifie sa vie. Or, l’individualisme de la pensée libérale ne saurait en aucune manière rejoindre ou justifier cette exigence. […] Toute l’éloquence passionnée du libéralisme s’élève contre la violence et le manque de liberté. Toute restriction, toute menace de la liberté individuelle en principe illimitée, de la propriété privée et de la libre concurrence se nomme violence et est de ce fait un mal. Aux yeux de ce libéralisme, seul reste valable, dans l’Etat et en politique, ce qui concourt uniquement à assurer les conditions de la liberté et à supprimer ce qui la gêne » [28].

En effet, il est marquant de voir à quel point la puissance de l’Etat diminue au fur et à mesure que l’idéologie libérale progresse tant au niveau économique qu’au niveau de ce qu’il est désormais convenu d’appeler sociétal. L’Etat est vu comme une contrainte à l’émancipation de l’homo economicus rationnel ne recherchant que son propre intérêt. Les privatisations des services publics, encouragées par le droit de l’Union européenne, sont à chaque fois accompagnées de discours promettant une diminution des coûts des prestations qui permettrait alors d’augmenter le pouvoir d’achat des individus. Toujours sur le plan économique, l’Etat est aussi sommé de se retirer au maximum pour permettre une totale liberté d’entreprendre aux individus (par la diminution des impôts, par la libéralisation des services publics, etc…).

L’Etat se doit aussi de respecter la liberté individuelle dans sa facette sociétale. C’est ainsi que, par exemple, le service militaire est supprimé par une loi du 8 novembre 1997 portant réforme du service national en faveur d’une seule journée d’appel de préparation à la défense. Ou encore, pour citer un exemple plus actuel, c’est ainsi que l’Etat par une circulaire du 25 janvier 2013 permet de délivrer des certificats de nationalité française aux enfants nés à l’étranger de parents français alors même que ceux-ci ont eu recours à la GPA pourtant interdite en France.

Le libéralisme économique renforcé par l’idéologie libérale-libertaire comme l’a si bien démontré Jean-Claude Michéa [29] pousse l’Etat à se diminuer. «Débrouillez-vous !» réclame Jacques Attali dans une tribune publiée par le magazine Slate le 2 avril 2014 [30]. Comme il l’explique sa «recommandation est claire : agissez comme si vous n’attendiez plus rien du politique. Et, en particulier, comme si vous n’attendiez que le pire du nouveau gouvernement». Il finit ainsi : «Accessoirement, l’agrégation de ces égoïstes et de ces altruismes privés aura un effet dévastateur et positif sur les politiques, en les poussant à justifier enfin leur raison d’être». Dans ce texte, Jacques Attali confirme totalement les vues de Carl Schmitt sur le libéralisme individualiste comme ennemi de l’Etat et du politique car, comme il l’explique, «si la négation du politique impliquée dans tout individualisme conséquent commande une praxis politique de défiance à l’égard de toutes les puissances politiques et de tous les régimes imaginables, elle n’aboutira toutefois jamais à une théorie positive de l’Etat et du politique qui lui soit propre» [31]. Le libéralisme ne peut qu’être dans un rapport de négation et d’opposition à l’Etat et à la politique. Il vide l’Etat de toute sa substance existentielle en le dépolitisant afin qu’il ne soit qu’un simple levier pour l’épanouissement individuel (devant alors, tout au mieux, ne garantir que l’enseignement scolaire, la construction des infrastructures et des routes nécessaires au commerce, etc…).

Le libéralisme économique renforcé par l’idéologie libérale-libertaire comme l’a si bien démontré Jean-Claude Michéa [29] pousse l’Etat à se diminuer. «Débrouillez-vous !» réclame Jacques Attali dans une tribune publiée par le magazine Slate le 2 avril 2014 [30]. Comme il l’explique sa «recommandation est claire : agissez comme si vous n’attendiez plus rien du politique. Et, en particulier, comme si vous n’attendiez que le pire du nouveau gouvernement». Il finit ainsi : «Accessoirement, l’agrégation de ces égoïstes et de ces altruismes privés aura un effet dévastateur et positif sur les politiques, en les poussant à justifier enfin leur raison d’être». Dans ce texte, Jacques Attali confirme totalement les vues de Carl Schmitt sur le libéralisme individualiste comme ennemi de l’Etat et du politique car, comme il l’explique, «si la négation du politique impliquée dans tout individualisme conséquent commande une praxis politique de défiance à l’égard de toutes les puissances politiques et de tous les régimes imaginables, elle n’aboutira toutefois jamais à une théorie positive de l’Etat et du politique qui lui soit propre» [31]. Le libéralisme ne peut qu’être dans un rapport de négation et d’opposition à l’Etat et à la politique. Il vide l’Etat de toute sa substance existentielle en le dépolitisant afin qu’il ne soit qu’un simple levier pour l’épanouissement individuel (devant alors, tout au mieux, ne garantir que l’enseignement scolaire, la construction des infrastructures et des routes nécessaires au commerce, etc…).

Le libéralisme a aussi pour particularité de favoriser la discussion au détriment de la décision. Donoso Cortés définit la bourgeoisie comme une «classe discutante», una clasa discutidora [32]. Cela se vérifie toujours actuellement. Défendant les mêmes intérêts et procédant à des alternances de majorité régulières qui ne sont que des changements de façade, les parlementaires bourgeois discutent sans prendre réellement de décisions car partant d’un même et seul postulat que le libéralisme est de toute façon l’unique système possible et donc qu’il faut y conformer l’Etat. Il est d’ailleurs frappant de voir à quel point la minorité parlementaire reproche à la majorité des réformes qu’elle souhaitait mettre en oeuvre quand elle était alors en majorité. Il ne s’agit évidemment que de postures favorisant une discussion perpétuelle au détriment de véritables décisions.

UN ETAT DISSOUS DANS LA SOCIETE LIBERALE

Selon la constitutionnaliste Marie-Anne Cohendet, l’Etat de droit (dans une conception matérielle) est un Etat «soumis à des règles de droit qui limitent son pouvoir et garantissent le respect des droits de l’homme, en particulier au moyen de recours juridictionnels» [33]. L’Etat de droit n’est en effet qu’un levier pour parvenir à la paix universelle, l’égalité entre les hommes, la liberté et autres valeurs universalistes découlant de la Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen de 1789. C’est ce qui amène Julien Freund à expliquer, en reprenant la pensée de Carl Schmitt, que «ce ne seraient plus les hommes qui gouverneraient, non plus que les lois particulières, mais seulement les normes générales et universelles. Autrement dit, la loi particulière n’aurait pas simplement valeur d’acte législatif, elle serait l’application spatio-temporelle de ces normes générales. Le résultat serait l’instauration du système clos d’une légalité souveraine qui n’aurait pas besoin de légitimité, parce qu’il ne reposerait sur aucun présupposé, étant donné qu’il serait légitime par lui-même, du fait qu’il accomplirait les voeux de paix, de liberté et de justice. […] En attendant que cet idéal s’accomplisse, il faut substituer à l’autorité du pouvoir la libre discussion des législateurs qui, dans leurs débats au Parlement, n’ont d’autre souci que de déroger, à la lumière de la raison, les voies les plus propices à l’avènement du système général des normes, grâce à la somme des actes législatifs ainsi accumulés» [34].

La loi du 17 mai 2013 ouvrant le mariage aux couples de personnes de même sexe en est un exemple parmi tant d’autres. Par cette loi, l’Etat a démontré qu’il s’érigeait en levier de l’égalité universelle entre les hommes en faisant fi des différences relatives à l’orientation sexuelle. En vérité, la dynamique universaliste de l’Etat de droit le pousse à légiférer dans des domaines relevant de la sphère privée des individus afin de réaliser le mythe de l’homme totalement autonome, libre et égal à tous les autres. L’Etat accompagne alors la dynamique libérale de la publicisation de l’espace privé et de la privatisation de l’espace public. Il en va aussi ainsi pour les débats parlementaires autour de la prostitution alors que l’activité sexuelle relève exclusivement de la sphère privée.

Dans ces conditions, l’Etat ne peut plus être décisionniste car pour qu’il puisse l’être il faudrait qu’il ne soit pas confondu dans la société mais au-dessus et à l’extérieur. L’Etat devient au contraire de plus en plus qu’un simple instrument de l’émanicpation individuelle, qu’un simple garant de l’individualisme libéral. C’est d’ailleurs pour cette raison qu’il y a une dépolitisation des individus, ceux-ci ne voyant pas l’Etat comme la personne morale suprême et extérieure prenant des décisons sur eux (auquel cas ils auraient tout intérêt à s’intéresser à la politique) mais comme celle qui au contraire porte par dessous l’individu dans une logique progressiste de subjectivation des droits.

QUE FAIRE ?

Face à ce constat de dépolitisation de l’Etat français, il serait trop facile et vain de vouloir revenir en arrière dans l’espoir de retrouver un Etat national puissant et véritablement décisionniste. Car contrairement à ce qu’en pensent les passéistes et autres Zemmour, cela n’est plus possible et ce pour deux raisons principales.

D’abord, face à l’uniformisation du monde accélérée par l’idéologie libérale universaliste, il est urgent de penser à une logique des grands espaces pour reprendre l’idée schmittienne, soit à une logique multipolaire afin d’éviter un monde unipolaire [35]. Ceci suppose que l’on doive raisonner à l’échelle de l’Europe plutôt qu’à la seule échelle nationale afin de préserver la singularité de notre civilisation ainsi que notre puissance. Il n’est certes plus sérieux de rester dans l’Union européenne de Bruxelles tout comme il n’est plus sérieux du tout de penser que l’on préservera notre civilisation, notre identité et notre puissance en dehors de toute coopération européenne.

Ensuite, face à la post-modernité naissante qui nous fait sortir de l’ère de la rationalité froide [36], vouloir revenir à un Etat moderne national, fort et centralisateur est une idée dépassée et un rêve illusoire. C’est pourquoi il faut désormais penser à une Europe forte, antilibérale, puissance politique et civilisationnelle (contrairement à l’Union européenne de Bruxelles qui n’existe que pour favoriser le libéralisme économique), préservant l’identité de tous les peuples européens dans une optique communautaire. Cela peut alors s’opérer grâce au principe de subsidiarité laissant place à de véritables démocraties locales.

1 : Jean et Jean-Eric Gicquel (2009) Droit constitutionnel et institutions politique, 23ème éd. Paris : Editions Montchrestien. p. 12 (Domat Droit Public)

2 : E. Clément, C. Demonque, L. Hansen-Love, P. Kahn (2000) La philosophie de A à Z. Paris : Hatier. 353 p.

3 : Jean et Jean-Eric Gicquel (2009) Droit constitutionnel et institutions politique, 23ème éd. Paris : Editions Montchrestien. pp. 12-13 (Domat Droit Public)

4 : Dictionnaire de français Larousse, http://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/d%C3%A9cision/22210 (consulté le 03/11/2015)

5 : Dictionnaire de français Larousse, http://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/action/924?q=action#919 (consulté le 03/11/2015)

6 : Dictionnaire de français Larousse, http://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/programme/64207?q=programme#63485 (consulté le 03/11/2015)

7 : G. Cornu, Vocabulaire juridique, 6ème éd., PUF, Paris, 2004, p. 369

8 : Jean et Jean-Eric Gicquel (2009) Droit constitutionnel et institutions politique, 23ème éd. Paris : Editions Montchrestien. p. 61 (Domat Droit Public)

9 : Ibid, p.62

10 : Ibid, p.63

11 : Ibid, p.63

12 : S. Guinchard, T. Debard, Lexique des termes juridiques, 18ème éd., Dalloz, 2011, p. 570

13 : Ibid, p. 349

14 : Hans Kelsen, Théorie pure du droit, 2ème éd. (1960), Dalloz, Paris, 1962, trad. en français par le Professeur Charles Aisenmann

15 : Carl Schmitt, Théologie politique (1922), Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1988, trad. en français par J-L Schlegel, p. 29

16 : Hans Kelsen, Théorie pure du droit, 2ème éd. (1960), Dalloz, Paris, 1962, trad. en français par le Professeur Charles Aisenmann, p.14

17 : Hans Kelsen, Théorie pure du droit, 2ème éd. (1960), Dalloz, Paris, 1962, trad. en français par le Professeur Charles Aisenmann, p.13

18 : « Il faut écarter radicalement le problème de la souveraineté » in Hans Kelsen, Das problem der Souveränität, Türbingen, 1920, p.320

19 : Carl Schmitt, Théologie politique (1922), Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1988, trad. en français par J-L Schlegel, p. 40

20 : Ibid, p.15

21 : Il s’agit d’une traduction recommandée par Julien Freund. Les lignes de force de la pensée de Carl Schmitt in Nouvelle Ecole n°44, printemps 1987, p.17

22 : Ibid, p.21

23 : Ibid, p.21

24 : Le Point, Pour Macron, passer par l’élection est un « cursus d’un ancien temps », http://www.lepoint.fr/politique/pour-macron-passer-par-l-election-est-un-cursus-d-un-ancien-temps-28-09-2015-1968726_20.php (consulté le 03/11/2015)

25 : P. Huet et J. Bravo, L’expérience française de rationalisation des choix budgétaires, PUF, 1973 ; J. Chevalilier, Science administrative, PUF, « Thémis », 4ème éd., 2007, p.490

26 : G. Dupuis, M-J Guédon, P. Chrétien, Droit administratif, Sirey Université, 11ème éd., 2009, p.23

27 : Site de La documentation française, La révision générale des politiques publiques (RGPP), http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/dossiers/modernisation-etat/revision-generale-politiques-publiques.shtml (consulté le 03/11/2015)

28 : C. Schmitt, La notion de politique (1932), Flammarion – Champs classiques, 2009, trad. en français par M-L Steinhauser, pp. 115-116

29 : Voir par exemple J-C Michéa, Le complexe d’Orphée, Flammarion – Climats, 2011

30 : Slate, Débrouillez-vous !, http://www.slate.fr/story/85455/debrouillez-vous-attali (consulté le 04/11/2015)

31 : C. Schmitt, La notion de politique (1932), Flammarion – Champs classiques, 2009, trad. en français par M-L Steinhauser, pp. 114-115

32 : cit. in Carl Schmitt, Théologie politique (1922), Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1988, trad. en français par J-L Schlegel, p. 67

33 : M-A Cohendet, Droit constitutionnel, 4ème éd., Montchrestien – Lextenso éditions, Paris, 2008, p. 190

34 : J. Freund, Les lignes de force de la pensée de Carl Schmitt in Nouvelle Ecole n°44, printemps 1987, p.19

35 : Voir la théorie du Grossraumordnung de Carl Schmitt dans Guerre discriminatoire et logique des grands espaces, éd. Krisis, Paris, 2011, trad. en français par F. Poncet

36 : Voir à ce sujet l’oeuvre de M. Maffesoli et en particulier son ouvrage L’Ordre des choses, penser la postmodernité, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2014

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Il ne s’agit pas de légitimer tel ou tel traité conclu par l’Etat français mais plutôt d’éclaircir la notion de souveraineté afin de justifier l’angle utilisé (la dépolitisation) pour analyser les causes de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat français actuel. Effectivement, il est courant d’entendre que si l’Etat est désormais faible politiquement c’est parce qu’il «n’est plus souverain». Or, comme nous venons de le voir, l’Etat français – qui a certes perdu son indépendance économique – est toujours souverain (sinon, on ne devrait même plus parler d’Etat). Aussi, ramener le problème de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat au seul problème de la souveraineté occulterait de l’analyse un bon nombre de causes de cette faiblesse.

Il ne s’agit pas de légitimer tel ou tel traité conclu par l’Etat français mais plutôt d’éclaircir la notion de souveraineté afin de justifier l’angle utilisé (la dépolitisation) pour analyser les causes de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat français actuel. Effectivement, il est courant d’entendre que si l’Etat est désormais faible politiquement c’est parce qu’il «n’est plus souverain». Or, comme nous venons de le voir, l’Etat français – qui a certes perdu son indépendance économique – est toujours souverain (sinon, on ne devrait même plus parler d’Etat). Aussi, ramener le problème de la faiblesse politique de l’Etat au seul problème de la souveraineté occulterait de l’analyse un bon nombre de causes de cette faiblesse. L’ère de la politique non politique est donc une uniformisation des décisions des acteurs politiques apparaissant comme neutres car relevant de la simple gestion d’un système économique libéral se présentant comme étant le seul possible. There is no alternative ou la fameuse formule attribuée à Margaret Thatcher est malheureusement la véritable croyance de nos petits technocrates actuels et cette croyance a largement accéléré le processus de dépolitisation de l’Etat.

L’ère de la politique non politique est donc une uniformisation des décisions des acteurs politiques apparaissant comme neutres car relevant de la simple gestion d’un système économique libéral se présentant comme étant le seul possible. There is no alternative ou la fameuse formule attribuée à Margaret Thatcher est malheureusement la véritable croyance de nos petits technocrates actuels et cette croyance a largement accéléré le processus de dépolitisation de l’Etat. Le libéralisme économique renforcé par l’idéologie libérale-libertaire comme l’a si bien démontré Jean-Claude Michéa [29] pousse l’Etat à se diminuer. «Débrouillez-vous !» réclame Jacques Attali dans une tribune publiée par le magazine Slate le 2 avril 2014 [30]. Comme il l’explique sa «recommandation est claire : agissez comme si vous n’attendiez plus rien du politique. Et, en particulier, comme si vous n’attendiez que le pire du nouveau gouvernement». Il finit ainsi : «Accessoirement, l’agrégation de ces égoïstes et de ces altruismes privés aura un effet dévastateur et positif sur les politiques, en les poussant à justifier enfin leur raison d’être». Dans ce texte, Jacques Attali confirme totalement les vues de Carl Schmitt sur le libéralisme individualiste comme ennemi de l’Etat et du politique car, comme il l’explique, «si la négation du politique impliquée dans tout individualisme conséquent commande une praxis politique de défiance à l’égard de toutes les puissances politiques et de tous les régimes imaginables, elle n’aboutira toutefois jamais à une théorie positive de l’Etat et du politique qui lui soit propre» [31]. Le libéralisme ne peut qu’être dans un rapport de négation et d’opposition à l’Etat et à la politique. Il vide l’Etat de toute sa substance existentielle en le dépolitisant afin qu’il ne soit qu’un simple levier pour l’épanouissement individuel (devant alors, tout au mieux, ne garantir que l’enseignement scolaire, la construction des infrastructures et des routes nécessaires au commerce, etc…).

Le libéralisme économique renforcé par l’idéologie libérale-libertaire comme l’a si bien démontré Jean-Claude Michéa [29] pousse l’Etat à se diminuer. «Débrouillez-vous !» réclame Jacques Attali dans une tribune publiée par le magazine Slate le 2 avril 2014 [30]. Comme il l’explique sa «recommandation est claire : agissez comme si vous n’attendiez plus rien du politique. Et, en particulier, comme si vous n’attendiez que le pire du nouveau gouvernement». Il finit ainsi : «Accessoirement, l’agrégation de ces égoïstes et de ces altruismes privés aura un effet dévastateur et positif sur les politiques, en les poussant à justifier enfin leur raison d’être». Dans ce texte, Jacques Attali confirme totalement les vues de Carl Schmitt sur le libéralisme individualiste comme ennemi de l’Etat et du politique car, comme il l’explique, «si la négation du politique impliquée dans tout individualisme conséquent commande une praxis politique de défiance à l’égard de toutes les puissances politiques et de tous les régimes imaginables, elle n’aboutira toutefois jamais à une théorie positive de l’Etat et du politique qui lui soit propre» [31]. Le libéralisme ne peut qu’être dans un rapport de négation et d’opposition à l’Etat et à la politique. Il vide l’Etat de toute sa substance existentielle en le dépolitisant afin qu’il ne soit qu’un simple levier pour l’épanouissement individuel (devant alors, tout au mieux, ne garantir que l’enseignement scolaire, la construction des infrastructures et des routes nécessaires au commerce, etc…).

Respectivement consacrés à Renzo de Felice et Giorgio Locchi, les chapitres 1 et 6 de la première partie posent les questions les plus fondamentales pour notre famille de pensée. Jusqu’où faire remonter la recherche de notre « moment zéro » (François Bousquet) ? Les étapes de la « tendance époquale » surhumaniste se succèdent-elles de manière continue ? Le fascisme lato sensu (dont le national-socialisme est provisoirement la forme la plus achevée) a-t-il été « prématuré (p. 142) », comme le laissent supposer certains passagers de Nietzsche prophétisant un interrègne nihiliste de deux siècles ?

Respectivement consacrés à Renzo de Felice et Giorgio Locchi, les chapitres 1 et 6 de la première partie posent les questions les plus fondamentales pour notre famille de pensée. Jusqu’où faire remonter la recherche de notre « moment zéro » (François Bousquet) ? Les étapes de la « tendance époquale » surhumaniste se succèdent-elles de manière continue ? Le fascisme lato sensu (dont le national-socialisme est provisoirement la forme la plus achevée) a-t-il été « prématuré (p. 142) », comme le laissent supposer certains passagers de Nietzsche prophétisant un interrègne nihiliste de deux siècles ?

According to Catharine McKinnon, the new mantra that should be taught to children is: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words are infinitely worse.”

According to Catharine McKinnon, the new mantra that should be taught to children is: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words are infinitely worse.”

Un suceso trágico de índole bélica impacta en la opinión pública, mediante los medios de intoxicación de masas (llamarle “medios de comunicación” sería convertirse en cómplices de las conspiraciones del poder), inmediatamente se desencadena un efecto sobre las masas, recogiéndose lo que se había calculado recoger: lo mismo la adhesión masiva a una intervención militar que la recepción de “refugiados”. El pacifismo fue empleado magistralmente por el comunismo soviético que, durante la Guerra Fría, lo exportó a sus sucursales en todos los países que permanecían bajo la férula estadounidense: se minaba así la combatividad de la opinión pública de los países capitalistas y se neutralizaba cualquier esfuerzo bélico procedente de los gobiernos. Dábase el caso paradójico de que, mientras en occidente los comunistas reclamaban la “paz”, los países comunistas seguían rearmándose. La lección ha sido aprendida por las demás potencias, independientemente de su signo político.

Un suceso trágico de índole bélica impacta en la opinión pública, mediante los medios de intoxicación de masas (llamarle “medios de comunicación” sería convertirse en cómplices de las conspiraciones del poder), inmediatamente se desencadena un efecto sobre las masas, recogiéndose lo que se había calculado recoger: lo mismo la adhesión masiva a una intervención militar que la recepción de “refugiados”. El pacifismo fue empleado magistralmente por el comunismo soviético que, durante la Guerra Fría, lo exportó a sus sucursales en todos los países que permanecían bajo la férula estadounidense: se minaba así la combatividad de la opinión pública de los países capitalistas y se neutralizaba cualquier esfuerzo bélico procedente de los gobiernos. Dábase el caso paradójico de que, mientras en occidente los comunistas reclamaban la “paz”, los países comunistas seguían rearmándose. La lección ha sido aprendida por las demás potencias, independientemente de su signo político.

Le titre du dernier livre de la collection des Insoumis, éditée par Les Belles Lettres, fait inévitablement penser, à une lettre près, au titre en français du célèbre film de Stanley Kubrick. Il donne déjà le ton de ce volume, celui d'un pamphlet assumé.

Le titre du dernier livre de la collection des Insoumis, éditée par Les Belles Lettres, fait inévitablement penser, à une lettre près, au titre en français du célèbre film de Stanley Kubrick. Il donne déjà le ton de ce volume, celui d'un pamphlet assumé.

Passionné dès son adolescence par les problèmes politiques et sociaux, Alexandre Zinoviev raconte dans ses mémoires,

Passionné dès son adolescence par les problèmes politiques et sociaux, Alexandre Zinoviev raconte dans ses mémoires,  Dans ses œuvres, Le Facteur de la Compréhension en particulier*, Alexandre Zinoviev note que la sphère idéologique comprend un grand nombre d'hommes et d'organismes dont la tâche consiste à conditionner l'esprit des citoyens dans un sens favorable à la survie de la société tout entière.

Dans ses œuvres, Le Facteur de la Compréhension en particulier*, Alexandre Zinoviev note que la sphère idéologique comprend un grand nombre d'hommes et d'organismes dont la tâche consiste à conditionner l'esprit des citoyens dans un sens favorable à la survie de la société tout entière.

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come.

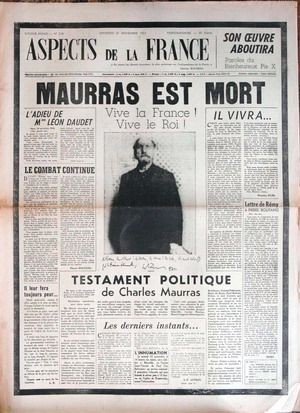

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come. So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.

So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.

Infatti, all’interno dell’opera

Infatti, all’interno dell’opera

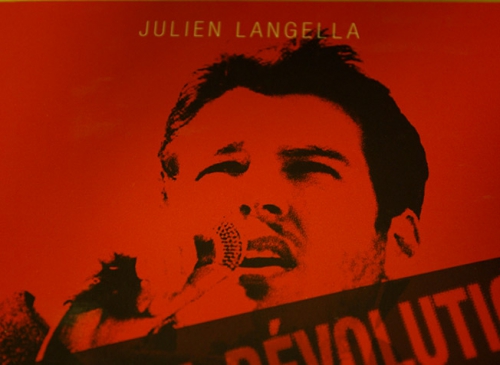

À rebours de cette mentalité hédoniste, « les jeunes ne sont pas bons qu’à être traders, banquiers, toxicomanes ou che-guévaristes du samedi soir. La jeunesse est d’abord l’âge de la volonté et de la vitalité, donc des possibles et des idéals (p. 12) ». Et Julien Langella d’illustrer cette quête des idéaux avec quelques exemples historiques européens. Outre les réfractaires au STO en 1943 qui grossirent les maquis résistants (il aurait pu évoquer le désintéressement d’autres jeunes volontaires dans une armée européenne d’alors pour le front de l’Est…), l’auteur mentionne la jeunesse de l’antique Rome républicaine. « À Rome, l’éducation traditionnelle est dépassement de la souffrance comme le courage est dépassement de la peur. De nos jours en France, le Blanc lambda apprend de sa cougar de mère que son père était un “ connard d’égoïste ” (p. 23). » Il revient sur l’importance exceptionnelle en terme de génération des Wandervogel allemands apparus en 1901. Créés à l’écart du scoutisme anglo-saxon, les « Oiseaux-Migrateurs » fuient par la marche et une communauté effective de vie et d’objectifs, le monde industriel. Certains groupes constitueront ensuite l’ossature Bündische de la Révolution Conservatrice. Plus méconnues et plus politisées existent à partir de 1903 au Pays Basque espagnol les Mendigoxales. Autant école de cadres du Parti nationaliste basque que mouvement de jeunesse, ces structures informelles concilient formation militante, randonnées en groupe et exploration des paysages pyrénéens. L’auteur rappelle enfin le cas de l’école Saint Enda à Dublin fondée en 1908 par l’indépendantiste irlandais Patrick Pearse. Ce genre d’initiative manque cruellement (ou demeure trop restreint) alors que s’effondre le système scolaire tant public que privé. Toujours en colère, Langella lance : « Un jour, on pendra tous les profs et les pédagogues qui ont joué aux apprentis-sorciers avec nos cerveaux. Un jour, vous répondrez de vos saloperies (p. 64) ». Il proclame plus loin : « Dynamitons l’école et ses gardes empaillés : transformons-la en un gigantesque bivouac au milieu des arbres et des cours d’eau, où l’on apprendra à devenir des hommes avant d’être une colonie de termites ! (p. 134) ». Julien Langella se réfère ainsi à Ivan Illich qui rêver de « déscolariser la société » ! « Dans les établissements scolaires, poursuit-il, au lieu de leur imposer des films indigestes et sans fin sur la Shoah, on diffusera des films comme Tropa de Elite, qui vante les méthodes viriles de policiers brésiliens en croisade contre les vendeurs de mort, ou Requiem for a dream, qui relate la descente aux enfers d’une bande de junkies (p. 121). »

À rebours de cette mentalité hédoniste, « les jeunes ne sont pas bons qu’à être traders, banquiers, toxicomanes ou che-guévaristes du samedi soir. La jeunesse est d’abord l’âge de la volonté et de la vitalité, donc des possibles et des idéals (p. 12) ». Et Julien Langella d’illustrer cette quête des idéaux avec quelques exemples historiques européens. Outre les réfractaires au STO en 1943 qui grossirent les maquis résistants (il aurait pu évoquer le désintéressement d’autres jeunes volontaires dans une armée européenne d’alors pour le front de l’Est…), l’auteur mentionne la jeunesse de l’antique Rome républicaine. « À Rome, l’éducation traditionnelle est dépassement de la souffrance comme le courage est dépassement de la peur. De nos jours en France, le Blanc lambda apprend de sa cougar de mère que son père était un “ connard d’égoïste ” (p. 23). » Il revient sur l’importance exceptionnelle en terme de génération des Wandervogel allemands apparus en 1901. Créés à l’écart du scoutisme anglo-saxon, les « Oiseaux-Migrateurs » fuient par la marche et une communauté effective de vie et d’objectifs, le monde industriel. Certains groupes constitueront ensuite l’ossature Bündische de la Révolution Conservatrice. Plus méconnues et plus politisées existent à partir de 1903 au Pays Basque espagnol les Mendigoxales. Autant école de cadres du Parti nationaliste basque que mouvement de jeunesse, ces structures informelles concilient formation militante, randonnées en groupe et exploration des paysages pyrénéens. L’auteur rappelle enfin le cas de l’école Saint Enda à Dublin fondée en 1908 par l’indépendantiste irlandais Patrick Pearse. Ce genre d’initiative manque cruellement (ou demeure trop restreint) alors que s’effondre le système scolaire tant public que privé. Toujours en colère, Langella lance : « Un jour, on pendra tous les profs et les pédagogues qui ont joué aux apprentis-sorciers avec nos cerveaux. Un jour, vous répondrez de vos saloperies (p. 64) ». Il proclame plus loin : « Dynamitons l’école et ses gardes empaillés : transformons-la en un gigantesque bivouac au milieu des arbres et des cours d’eau, où l’on apprendra à devenir des hommes avant d’être une colonie de termites ! (p. 134) ». Julien Langella se réfère ainsi à Ivan Illich qui rêver de « déscolariser la société » ! « Dans les établissements scolaires, poursuit-il, au lieu de leur imposer des films indigestes et sans fin sur la Shoah, on diffusera des films comme Tropa de Elite, qui vante les méthodes viriles de policiers brésiliens en croisade contre les vendeurs de mort, ou Requiem for a dream, qui relate la descente aux enfers d’une bande de junkies (p. 121). »